La Guajira Peninsula: a Grandiose Adventure into a Surreal South American Setting

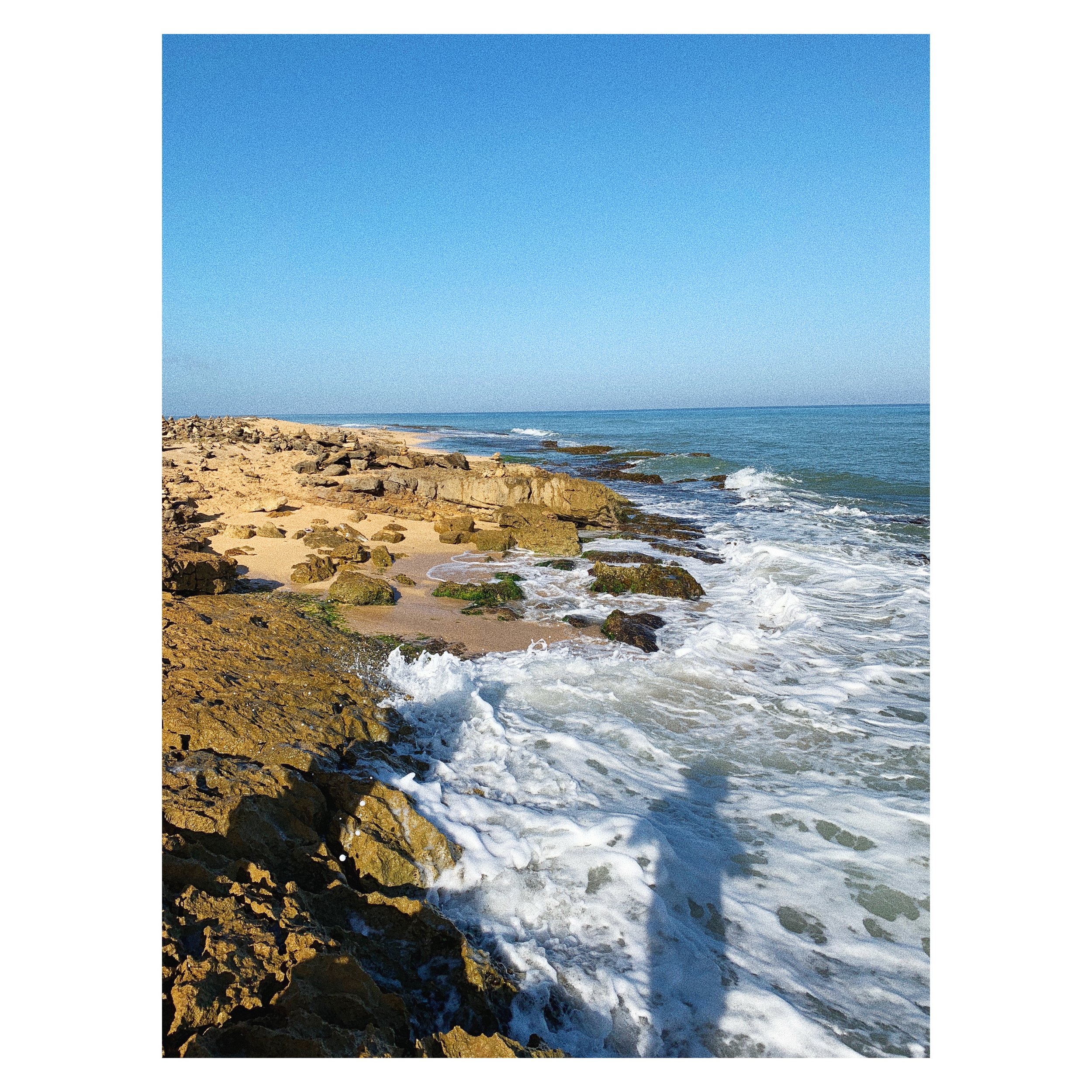

From Riohacha, a small coastal town with strong Afro-Caribbean roots in northern Colombia, we (the three Californian musketeers) set off on a three day off-road expedition through the La Guajira peninsula. Home to the indigenous Wayuu (descending from the Tayrona ancestral tree) who withstood conquest from the Spaniards, La Guajira is an unforgiving, yet breathtaking landscape of salt and sand where the desert and sea converge into a candescent cacophony of splendor. Guajira offered a scintillating spectrum of settings: sand dunes sloping softly down into the azure waters of the Caribbean sea, rocky mountain cliffs buttressing the desert from ocean waves, hammock hangouts on seashell lined beaches, and coastal sunsets weaving bright, vivid hues into the clouds and sky like a Wayuu handbag.

In 3 days we hit most of the key stops: Cabo de la Vela--a kite-surfing hotspot where we were treated to the full spectrum of constellations and bioluminescent plankton by night; Pilón de Azucar and it's dazzling display of color--emerald and aquamarine waters, dark gray and black rocky cliffs, orange gold sand that enveloped my feet like a blanket, and clear blue skies; Ojo an el Agua for an uncanny sunset redefining the word vivid; the Taroa Sand Dunes with silky soft sand sloping down into the shimmering sapphire sea (felt like I was living a scene from The Alchemist); Playa Agujas for another spectacular sunset that reminded me of sunsets descending behind Catalina island in California; Faro Lighthouse where the infamous Colombian narco-terrorist Pablo Escobar used to send his cocaine carrying planes to the U.S.; and the rocky shore of Punta Gallinas--the most northern point of all South America. For one sentence that was a lot to include, and for our three day journey it was even more. It was truly a whirlwind of a weekend

While the scenery was supremely stunning, equally as shocking was the stark poverty of the Wayuu people. During the whole offroad journey in the desert--from Uribbia the gas town to Punta Gallinas--I would guess that we encountered at least 50 "chicken check points," where local children and women had strung up makeshift barriers across the road. These "barriers" (if you could even call them that) were composed of tied handkerchiefs, clothes, rope, and random pieces of cloth or fabric, and sometimes included a bike chain; however, both ends were either connected to tiny shrubs or cacti, and often times one end was held in the hands of a Wayuu youth (who could definitively not resist the forceful momentum of a passing car.) The hope was never to stop a passing car, only to slow down the caravan enough to ask, or beg, for money or dulces (sweets) with arms outstretched and palms up.

It was a heartbreaking level of poverty that I had not encountered before, different than the widespread homelessness crisis in San Francisco that renders thousands to a life sleeping on city streets. In La Guajira, there was no telling how the quality of life was for these people, but I could certainly make a guess. Our driver, a Wayuu named Moura (who had 2 wives and 8 kids, as polygamous Wayuu culture permitted) told us most of these indigenous lived in hammocks, in huts or small houses made from earthen materials, and ate what little the desert and their goat herds provided. It was a cosmic slap in the face to my privilege, and a reminder that the world is a much bigger place than the bubble of Orange County, or L.A., or San Francisco, or even California. In that wide world it isn’t always so neat and pretty, fancy or materialistic, or anything remotely resembling vapid U.S. society—and empathy is vital to understanding and opening yourself to the world. When I say the poverty I saw was heartbreaking it is because I felt totally helpless; I simply have no clue what I could do to help the Wayuu other than share what sweets and coins we had with them. Hopefully, my experience—shared in photos and words here—can in some manner make the story of the Wayuu more visible so that change can come in the future.